To all Catholics, and all people of good will: May grace and peace be yours from the Father, through the Son, in the unity of the Holy Spirit!

I am an autistic Catholic priest.

My unusual identity gives a particular twist to how I am called to live out my priesthood. In the ancient world, one of the images used to describe the priest was pontifex, Latin for bridge-buulder. We still use this term when we refer to the Pope as the Supreme Pontiff. The role of the priest was seen as building a bridge between divinity and humanity. Since Jesus Christ, by His Passion, Death, and Resurrection, reconciled us to the Father in the Spirit, He became known as the true High Priest, the ultimate bridge-builder between God and humanity. All Catholic priests, from that time on, have been given a share in His work of bridge-building. Some exercise this in parish ministry. Others serve as hospital or prison chaplains. Still others dedicate themselves to specific groups of people who are in need of shepherds and bridge-builders.

I had been in parish ministry until the effects of my autism and my growing sense of a calling to devote myself to a more contemplative form of priesthood led me to retire from parish ministry. However, my calling to build bridges remains. The Lord has shown me that an important part of my vocation now is to be a bridge-builder between the Lord, the Church, and autistic people. I seek to do this through this blog. I seek to do this through the Autism Consecrated website. I seek to do this through a life devoted to prayer as a contemplative hermit in the Lord’s presence. It is in this role as bridge-builder that I address you now.

Autism is considered to be a disabling condition. If you are diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder and meet certain criteria, you can qualify for Social Security Disability in the United States. As a nation and as a Church, we still struggle to make our churches and public spaces accessible to people with disabilities in general. Many of our churches may have wheelchair ramps. Some may have people who can interpret the words of the Mass in sign language for our deaf members. It’s the rare parish that offers more than this.

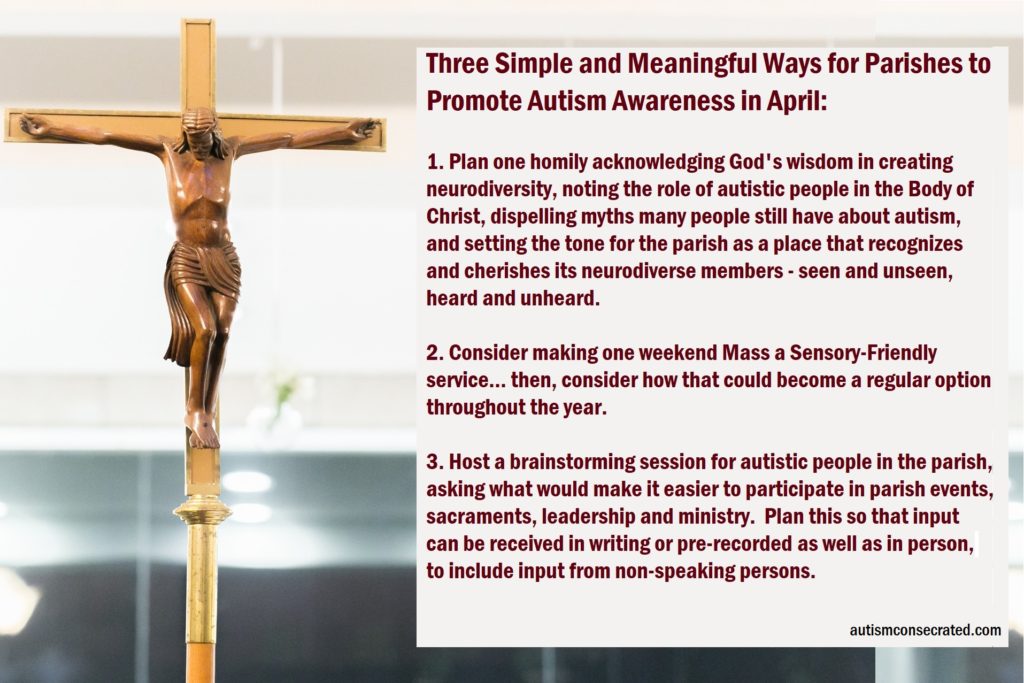

What about the needs of autistic Catholics? Most of the books written (so far) on autism and Church have been written by Protestants. Those written by Catholics are chiefly focused on how to adapt a faith formation curriculum for autistic children. People forget that those children grow up! A few parishes have set up “sensory-friendly” rooms (anti-cry rooms, so to speak), separate from the main worship area. These rooms feature (ideally) softer lighting, lower audio volume, and a TV screen for watching Mass. Having spent time in one, I can say that such rooms cut both ways. On the one hand, they are a positive help. On the other, people who use these rooms are easily forgotten by the parish community, even its leaders, because they are unseen. A few dioceses are trying “sensory-friendly Masses”. These are Masses in parish churches, in their usual worship space, which feature lower audio volume, softer lighting, and other tweaks. These Masses are a step in the right direction.

The biggest challenge, however, isn’t about buildings or programs or even sensory input. It’s about attitude. Do you want us? Do you, my dear fellow Catholics, want us autistic Catholics as part of your faith communities? If the attitude is there, the rest will follow.

This is an extremely important question. One recent survey has shown that over 80% of autistic Christians (Catholic, Protestant and Orthodox) do not attend services in their local churches. This is the highest percentage of non-attendance of any group with a disability that still leaves them capable of going to church. Slipping into my logical brain, I would assume that this statistic alone would make autistic Catholics (and other autistic people) a prime focus of the New Evangelization. I would assume that this would make autistic Catholics an ideal target for the New Apologetics that Bishop Robert Barron and his Word on Fire community speak about. The harvest is indeed rich. Where are the laborers?

When I could see that I could no longer do parish ministry, I proposed to officials in my diocese that I could be a consultant or liaison for ministry to autistic people in my diocese. No one showed interest in this. Diocesan officials say that the local parishes should do something about this. Local parishes say that they lack the resources for this.

That is not all. I regularly hear from autistic people who have tried to connect with their parishes and find that they are ignored, their needs minimized, and their behaviors (over which they may have little control) ridiculed or mocked – even by pastors and lay parish leaders. Many autistic Catholics end up feeling like they have to pastor themselves. Is this right? Is this what Christ had in mind for His Church?

It doesn’t help that autism is seen by many as a “mental illness”. Even in 2022, when people see the term “mental illness”, they are much more likely to think of serial killers and mass shootings than the story of a group of Down’s Syndrome adults who had a foot race in a Paralympics. The ones who took the lead then slowed down so that all the runners could cross the finish line together and win together.

Let me be blunt. If we autistic people were all wealthy, parishes and dioceses would beat a path to our doors. If we were members of a favored group in our culture, some Church ministers would reach out to us, if only to score points with society as a whole. Far too often, Church leaders take their cues (even without realizing it) from the prevailing cultural standards and not from the Gospel. We matter only if the surrounding culture says that we matter.

The Gospel has a different narrative to propose to us. Christ offers us the parable of the man who had a hundred sheep. One of them runs off. In first-century Palestine, anyone wealthy enough to have a hundred sheep could easily replace the missing one. Yet the shepherd leaves the ninety-nine in search of this one sheep that had no worldly value.

Saint Paul gives us more guidance. The community he founded in Corinth was beginning to think highly of itself from a worldly point of view. They believed that they had “made it” in the world, and looked down on those (even of their own Christian community) who had no worldly status. Saint Paul reminded them, first of all, that most of them had little worldly status when they first embraced the faith. Moreover, they are now members of the Church, the Body of Christ, where all cultural values are inverted. Those who seem to be worthless in the culture’s eyes are all the more valued by Christ and should be all the more honored by all His disciples. Every Catholic community, from then until now, shows its understanding of the Gospel by how they love those people who are deemed to be lowest in the society around them.

Autistic people, at first glance, may not seem attractive or promising candidates for a Catholic community. We have trouble reaching out and expressing our feelings, even feelings of love. We may seem cold and uncaring to those who do not know us. We can move in odd, repetitive ways, make sounds unexpectedly, or have meltdowns in public. We wear headphones to church to protect us from the audio volume (which may be too loud even for you) and we are accused of disrespect as you assume we’re listening to music.

If there is anything you can learn about us, let it be this. We are like you in many ways. The things that bother you, bother us. Where we differ from you is not in kind, but in intensity. Imagine an equalizer. In some areas, our settings are like yours. In others, the settings are turned way up – or way down. Some of us are extremely sensitive to sounds, or colors, or certain smells or the feel of certain things. Some of us are very sensitive to inconsistencies and incongruities and cognitive dissonance. If you claim to believe one thing and live another, we see it immediately. Given our lack of social skills, we might even say so. This may not ingratiate us to you!

Nevertheless, we have souls and hearts. We are human beings. Christ died for us as He did for you. Our salvation is as important as yours. The fact that we are human, like you, should be more than enough for you to reach out to us and work with us to help us become part of our Catholic communities as best we can.

Now I’ll let you in on a little secret. We have a special gift that comes from being autistic. Think of the odd behaviors we may exhibit – the movements, the noises, the meltdowns, the anxieties. Some of these, at least, are in fact given to us for the community as a whole. How so, you ask?

Think of the old story of how miners would bring caged canaries with them into the mines. The canaries were more sensitive to poisonous gases than the miners, so the gases affected the canaries first. When the miners saw this, they knew they had to leave that mine, and quickly. In the same way, if an autistic person reacts very strongly to the sound volume, or to poor sound quality, this is a problem that will affect everyone eventually. Rather than blame the autistic person, look at the problem this person perceives. If an autistic teenager can’t deal with youth ministry as most parishes do it, maybe the problem is with the way youth ministry is done. I read about a teacher who decided, as an experiment, to change the way she ran her classroom to accommodate her two autistic students. When she did so, she found that everyone did better, not only the autistic students.

What the world deems foolish is often wisdom before God.

There is much more I can say; much more I can offer in regard to all this. If you want to pursue this, you’ll find some other posts in my blog and a lot of the material in Autism Consecrated to be most helpful. Please remember: Christ died for us autistic people, too!

May the Lord generously bless all of you, all that you do and all that you are!

Father Mark