“Incarnation” literally means “taking on flesh.” Jesus’ Incarnation is that moment when God took on human flesh – fully God, fully human. As with our discussion of the Holy Trinity, these tenets of the Catholic faith are impossible to state in the kind of factual terms we might use to describe the natural world. The Catechism is not a scientific proof; it is an outline of what is offered when we accept the invitation to believe. There are no words or experiences with which to relate supernatural realities beyond our own. Instead, we are invited to believe in Jesus Christ, God-With-Us, God-Made-Flesh, as proof of God’s love of, and investment in, humanity.

Lesson Seven goes into much useful detail about why the Incarnation took place, and it is well worth reading. [Link here and search “Lesson 7”]. But what of our annotation for autistic thinkers? How do we truly make a connection with something this inexplicable, yet – especially at this point in December – visibly depicted everywhere we look?

The Annotated Catechism approaches matters of faith by asking, “What is being described? How does this pertain to me as an individual, and what is my role?” Simply: our role is to be human – to have a soul and a body, to have free will and curious intellect, deliberately and individually designed, and given by God.

Within that makeup, however, is the stain we inherited from our ancestors’ disobedience, resulting in a distrust of humanity’s goodness and doubt surrounding God’s designs. God warned that the consequence of disobedience would be death… not immediately, but instead of enjoying perpetual blessing, disobedience forfeited our bodily protection from pollution, decay and death.

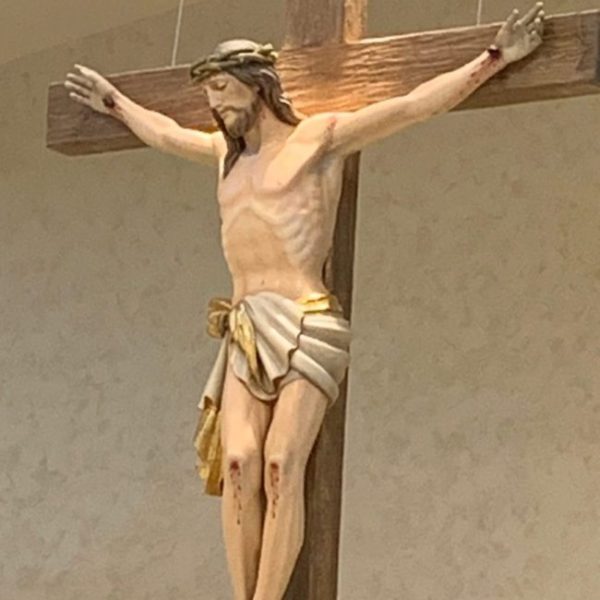

Few reflexes are as primal and universal as the way we recoil in the presence of rot and flinch at imminent death. “Thriller” films and novels evoke adrenaline for some and horror in others, but the same instinct is at play. Even as many of us believe firmly that crossing over is the pathway home to God, there is an instinctive bodily opposition to pain, suffering and, ultimately, death. This brings us to that paradoxical statement we sometimes hear in the course of evangelization: “God was born so that he could die.” In all truth, that is a good way to sum up the Incarnation. We also hear that “The sinless Jesus bore the stain of sin for us.” But what does that mean?

Bishop Thorlak of Iceland was deeply influenced by the theology of Hugh of St. Victor, who explains the Incarnation in systematic terms of God’s desire to break through our barrier of distrust with demonstrable love. The following insights come from Hugh of St. Victor’s De Sacramentis, Book Two, Part One.

First, some relational definitions. Since God is Creator of all and Authority over all that is created, He cannot obey, as there is no authority outside Himself. He cannot be sent forth, as there is none who might send Him. He cannot choose between right and wrong, because He is Truth and Knowledge itself. And, God cannot die, as He is all in all of all.

Next: Our relationship with God was broken when our first ancestors disobediently ate the fruit which awakened the choice of exploiting God’s goodness for our own, solitary gain. This gave rise to vice, which is the natural consequence of sin, and brought bodily death upon the human race as the final means by which our disordered inclinations can cease to plague our senses. Humans have no natural ability to liberate ourselves from this inherited pattern.

God, grieving this consequence, knew that the only way to change this sequence without unraveling the makeup of humanity would be to somehow graft our broken nature back into the Godly line. The logistical problem is that our nature is human, not Divine; and only God is God.

While humans cannot become God, could God become human? Technically yes, but that would require his radically changing form and abdicating His Divinity, which would disintegrate all of Creation. In order to reverse the curse affected by our ancestors, God would need the capacity to freely choose and obey, which (as shown above) is not possible if he remains Divine.

However: A son bears the name and inherited essence of his father. A son with a human nature can freely choose to obey. A son can be sent to carry on a father’s mission and values, becoming his de facto representative where he is sent.

Thus, God did not come as Creator to our earthly plane. He sent His Son, born human of a human mother, with a human soul, free will, and earthly flesh. Being born of Mary, who was preserved from inherited (original) sin, the Son would not have the same fallen focus self-gratification that other humans have; yet He would physically exist within the parameters of humanity – including subjection to bodily decay and death.

So: God sent a Son, Jesus, bearing His nature, to the womb of a mother free of original sin, so that He could live as a human, and die as a human. God’s Son would act to reverse our disobedience, completely innocent of any vice but still obedient to the bodily the penalty of sin – death. It is the equivalent of an innocent man offering to take the sentence of a convicted criminal, and serving it faithfully to its completion.

But… why?

We offer this admittedly oversimplified, but hopefully helpful analogy, addressing the question of God taking on the stain of sin and subjecting Himself to bodily death. Imagine God as an endless body of life-giving water free of all pollution. When humanity partook of sin, we became splattered and caked with toxic waste, with no way to purify ourselves. Dwelling directly with the water of God was no longer an option for us as we would poison all of Creation with our presence… but at the same time, that water is the only means by which we can detoxify from the pollution of sin.

How can we solve this conundrum? We can’t return to Him polluted, and if God Himself were to descend, He, being pure water, would devastate and drown us! But what if this pure water (God) could supernaturally take human form? He would be a living, infinite source of life-giving water, simultaneously existing as, and contained by, a physical human body. As God, He would be free of our pollution… but, would willingly mingle with us, acquiring more of our stain each time He infuses us with life-giving water. He will dilute our sinful inclinations, that is, our toxicity, to the degree we accept His gift. Some of us shrink back and say we are too dirty to ever think of mingling with God… some say that pollution is not bad and prefer to remain in the toxic state… and some will draw water from God’s Son again and again, wishing one day to return to that state of grace our ancestors knew before the stain of sin came into our line. God, for His part, gives without account, as often as we wish, as often as we trust, as often as we accept. He always invites, and never forces.

[Following our analogy to its conclusion: God’s human body eventually succumbed to the effects of our pollution. But, being supernatural, it was only the physical, earthly form that died. God knew that an earthly body could not live forever in our realm, so He made provisions for that in His scenario, which would include resurrection and establishment of a wider body, The Church. That is an entirely different discussion for future commentary!]

This is all little more than a sketch which cannot compare to the deeper theology at hand. For here, for now, let us conclude by revisiting our thought, “What is the Incarnation? How does it pertain to us, and what is our role?” May we find our answer close in our hearts.