Mercy, Unmasked

Easter has come! Alleluia! No virus can destroy our faith and hope in the Resurrection!

Can it?

No, assuredly, not. There is plenty of evidence to the contrary. People are clamoring more than ever for a taste of God, and we are doing everything within our creative power to stay connected to our faith communities in any way we can. Every social media page is filled with encouragement and song, even “COVID-cover” songs to parody the virus that has redefined every aspect of normal existence.

The liturgical calendar is just getting started with the celebrations, with Easter being (of course) the greatest and highest of our feasting. But besides giving us fifty days dedicated to proclaiming victory over death, the Church gives us a feast-within-a-feast, Divine Mercy Sunday, which adds dimensions of depth reaching far beyond simple celebration. Mercy Sunday deepens the Easter celebration to encourage us to realize there is even more: more growth, more life, more realization of what it truly means to have witnessed Christ now proclaimed, denied, condemned, killed, mourned and resurrected.

What an interesting time to come upon the Feast of Divine Mercy. Who among us is not eager to pray for mercy? The world begs for mercy… upon those dying from COVID-19 complications… upon healthcare workers and first responders… upon families who are diligently following every protocol to protect their weak and vulnerable members… upon those whose needs must be set aside to prioritize the response to the pandemic… upon those who are unemployed, or without food, or whose housing and basic necessities are jeopardized by the shutdown of businesses. The list is overwhelmingly long.

It is an understatement to say that our coping resources are stretched to their limits, no matter who we are, no matter what we carry in our daily rucksacks of needs, challenges and obligations.

It is burdensome to imagine adding any more challenge to the mix. I pray this is explicitly clear to those reading this post: There is nothing in my intended words meant to suggest that any reader is not doing enough, not making the most of what we can with what we have, and not responding with faith and love in the midst of all the rapidly changing mental, spiritual and physical demands.

In the spirit of building ourselves and each other in faith, then, we have the opportunity to pray for Divine Mercy.

For the past month and beyond, our civic leaders have done an excellent job communicating what we need to know, and do, to maintain our physical safety. We have been given clear visuals on how to sanitize our hands and surfaces we touch, where to stand to maintain safe distance, and even a very concise explanation of the statistical models being used to predict the best chance at containing and minimizing the devastation that might result from the worst-case scenarios. It has taken a few weeks to adjust and adapt, but for the most part, we are functioning as a society within very different physical guidelines, and doing a remarkably good job.

Now that we have had this time to digest, assimilate and adapt, we can begin considering how these changes might impact our spiritual health and well-being.

Readers of the Mission of Saint Thorlak will recall several themes on this topic over the past three years. A brief synopsis might be:

- Health of the body must first hinge upon, and flow from, attention to health of the soul

- Health of the soul comes from recognizing and embracing our vulnerability and common human needs

- Self-preservation is a pattern that shuts others out, eventually shutting out our openness to God

- Love casts out all fear

- Mercy is rooted in trust

The following is an excerpt from “The Divine Mercy Connection,” published by the Mission of Saint Thorlak in February, 2018:

Numerous teachings on Divine Mercy have been proclaimed by saints and theologians of recent time to counter the despair, fear and littleness we experience with the expanding awareness of evil in our age. Thousands hear and turn toward God in the comfort of this loving embrace. Yet, thousands more miss the window, maybe not even knowingly, by practicing the culture’s habits of humanism, relativism and individualism with dysphoria and distrust. Thousands fortify themselves in self-esteem, self-justification and self-preservation because it is the backbone of individualism. Such mindsets may be great for self-empowerment, but ultimately, they impede and reject mercy because they do not perceive any use – any need – for it.

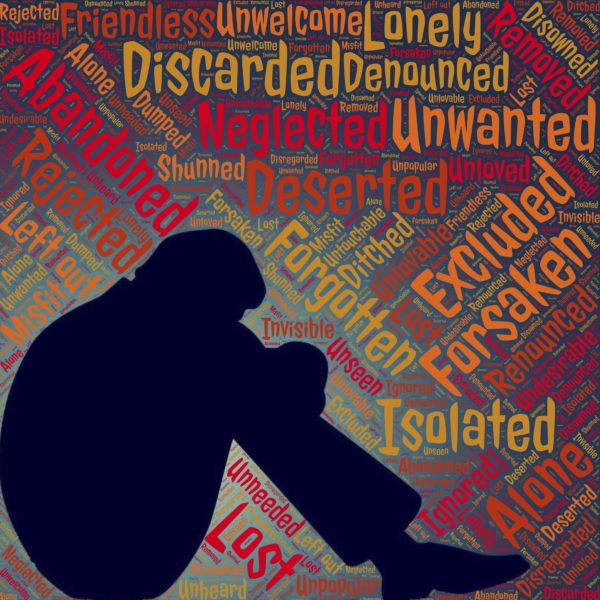

Brokenness [vulnerability] permits mercy to penetrate the shell of self-reliance. It is through our vulnerability that mercy reaches us. Need is the most fundamental common denominator of humanity. We are all weak, or broken, or needy in some way. Being comfortable with weakness will win the battle of spiritual deprivation because need is not a weapon… it is our supply pipeline… our very lifeline. Without need, life has no purpose. Even the staunchest individualist can be persuaded to see – and experience – the validity of this argument.

Need opens doors.

If we have no place for need, we cannot understand mercy; because, without need, mercy is meaningless.

Revisiting these words seems almost foreign after weeks of learning how to protect ourselves, isolate ourselves, fortify ourselves and reduce vulnerability.

It is absurd to suggest that we should ignore the safety of ourselves or others, and that is not at all the purpose of this post. But now that we know how to be physically safe, and as we come up on Divine Mercy Sunday, I wonder if it is an acceptable time to reintroduce vulnerability, on a spiritual level… or, if that word has now become hopelessly associated with something to be shielded, fortified or avoided?

Let us start by thinking about the masks many are wearing at the urging of health officials. I am not referring to those treating coronavirus infections on the front lines, whose masks are critically important. I am referring to the rest of us, whose masks are nonetheless important, but in the sense that they shield us from the potential of being unknowingly exposed to an unseen threat.

C.S. Lewis posed the question through the voice of Orual: “How can [God] meet us face to face, till we have faces?”

In similar vein, I ask: How do we pray for mercy unless we are open to what mercy asks of us?

How do we pray for mercy during a time when physical safety requires shielding ourselves?

Now that we have learned how to lock down, how do we learn how to open up again?

If we go deeper, we can begin to ask the harder questions, with sincere honesty and humility: For whom, for what, would we risk exposure? For whom, for what, will we take off our masks? What would Divine Mercy compel us to respond? And what if, after weeks of fear, our hearts are not yet ready?

May this be a beginning of an authentic, renewal of Mercy, for which we each might pray.