ACAT 4: The Process of Relating to God

[Readers, please note: Ordinarily, the respect due to God is expressed by capitalizing the H in pronouns. However, writing about familiarity in relationship requires a lot of these pronouns – and that capital H is becoming distracting. God deserves respect, yes; but he does not demand it to the point of distraction. We considered what it would mean to drop the capitalization in favor of increasing comfort and familiarity, and it feels right. We mean no disrespect to God by using lowercase pronouns. We offer it to God, in love, as a sign of our desire to grow closer in familiarity with him, intending no offense.]

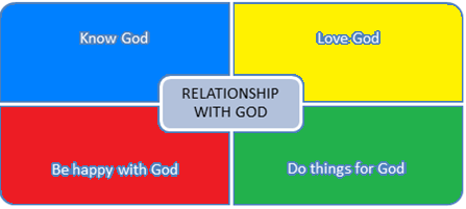

Last week, we began looking at the Baltimore Catechism’s proposal that God created us to know him, love him, serve him and be happy with him in the life to come.

We suggested seeing this first as a task list given in order of importance, with each step intended to prepare us for the next, flowing with a natural logic. We can’t love someone without knowing them. We can’t serve someone without loving them (and, before any buzz starts, we already have Missionary Thoughts lined up to go more deeply into that word “serve,” especially wondering how it can lead to happiness when it sounds so contractual).

Yes, each step is a foundational block, and each successive step builds further on the previous one.

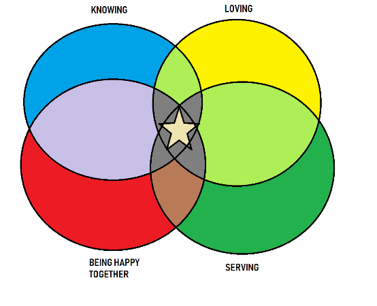

But it is not a flat, linear progression. It is a dynamic process, a progression of modules leading one to the next and then building upward, constantly adding more layers for each completion of the cycle, day after day in our lifetime. The four together are a constant, living process.

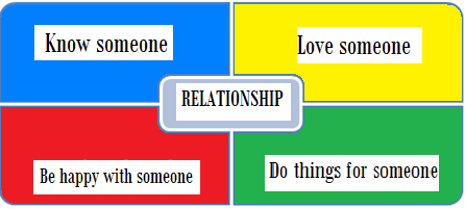

This process, in fact, describes building a relationship with anyone:

When an enduring relationship is forming, what we discover about someone (= getting to know them) eventually gives rise to a particular fondness. We can feel this as we feel love toward our family members, or toward our friends, or in the general sense of the value and dignity we feel toward others. But then, we begin to concretely “love” in the verb sense by showing affection, or speaking affirming words, or including people in our activities as we might invite a friend, a guest or someone on the sidelines without a partner to participate in what we are doing. We love by giving gifts, making food and welcoming visitors. Loving can be offering to drive somewhere, or answering the phone when we are already tired, or forgiving those who overstep their boundaries with us. If we notice, knowing (taking in concrete, measurable data) gives way to loving (forming an abstract conclusion) which gives way to doing, or serving (concrete action motivated by abstract feeling).

Thus, loving forms the bridge between knowing and doing (or, serving), which leads to being happy with each other in the relationship. As each module augments the other in the process, a foundation is formed. The process repeats and repeats and repeats in the rhythm of the relationship, as though placing bricks one atop the other in an ever-growing structure.

So, how easily can we replicate this process when our someone (God) is not three-dimensional?

Knowing: Books, videos, homilies and Scripture are some of the many formal ways we can know God, but evidence and ideation of God occurs frequently and much less formally. Imagination can be the best tool for us to encounter God interiorly and to make deeply personal and emotionally relevant observations that will help us know him better.

Loving: Can we yet sit back and reflect on what we are reading, what we are hearing about God, what we see in creation around us, through natural beauty and the love of animals, and feel a connection with – even a fondness for – God? Maybe so… or, maybe not yet. Maybe it comes and goes. If all we do is believe he is there, eventually, we’ll find him… but only if we pay him attention and remember to include him. He is just like any one of us who are not easily seen or heard above the others in the room. Silence does not mean he is not interested and not participating in our lives.

Serving: Moving from the abstract toward the concrete, how can we enact our love of God by responding to what we know about him? How are we to know what delights him, what needs he has, or what he might ask as a favor? We can’t give God rides to the store, or buy him gifts, or make him dinner. We can’t listen to his hard day’s work stories or let him stay an hour past when we told him we had to go. However, in Matthew 25:35, Jesus says, “When you do it for the least among you, you do it for ME.” We can love God by loving his proxy, the person in front of us. Service becomes a tool to discover and express our love, not a mandate – but more on that next week!

Being Happy With God: Relationships take time. Few of us are ever lovestruck instantaneously, but rather, we cultivate familiarity and comfort by giving our attention to knowing others here and there until they becomes part of our everyday and less an awkward silence in our lives. The same is true of God. Loving God means feeling the comfort of his being silent with us the way we welcome our friends to be silent with us… and to let us comfortably be silent with them.