A Lenten Daily Prayer Calendar to Realize Autism’s Belonging in the Body of Christ

Jesus, Re-member Us!

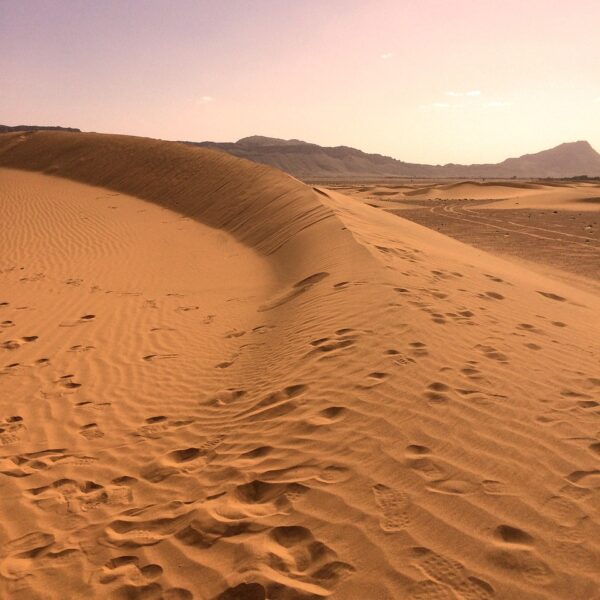

Lent necessarily evokes a certain imagery of journey: a voluntary withdrawal to a place of self-scrutiny to shed habits acquired from the world’s false theology of power, utility, and convenience, followed by a going forth with new resolve and better understanding of God’s intended Way. We often refer to this as a pilgrimage to the desert, evoking the literal path taken by Our Lord (and Israel before him) dedicated to prayer, self-emptying and preparation for the mission ahead. Desert life is likewise well-suited to pilgrimage, in that there are few places of concealment. The bright, hot sun starkly exposes who we are and what we carry with us, including aspects of ourselves and our habits which we might prefer stay hidden in our interior shadows; yet we soon realize the necessity of letting go of superfluous cargo if we are to survive the journey. Likewise, the desert’s vast stretches of isolation provide an environment free of diversions which might delay our reckoning. And then, the scarcity of resources reminds us unambiguously of our utter dependence on God, as well as the needs and interdependence of every member of the Body – both literally in our our own physiology, and figuratively in our reliance on mutual support within our communities.

For many autistic people, we are already in the desert. We are isolated, hungry, thirsty, and out of range of communication. We send signals, we explain our needs, we offer our services – but we are not seen, heard, or understood. It very much feels like involuntary exile without a clear or valid reason.

This experience is not unique to autistic people; indeed, the Church itself knows what it feels like to be excluded and isolated from secular society. In similar fashion, the Church communicates the Gospel message in many ways, yet is often not heard or understood. Nobody would argue that the Church is neither valued by contemporary society nor has much influence on public policy or cultural mores. It would be fair to say that the Church today finds itself in a very similar place as regards the secular world as autistic people. Wouldn’t it seem, then, that the experience of autistic people – who are very familiar with this sort of desert living – might be a great asset, and a source of wisdom, to the Church as a whole?

Unfortunately, autistic people are not only exiles from the cult of normalcy at large in the world. We are equally marginalized within the Church, the Body of Christ, by leaders who routinely ascribe to and apply the same standards as those held by that same secular cult of normalcy. A glance through our previous blog posts bears this out all too abundantly. To be fair, there are numerous parishes and dioceses who do take an active interest in supporting neurodivergent needs, and for these, we are truly grateful. We are not suggesting that the landscape is completely barren or bleak. We are, however, painfully aware that there are still many wounds yet to be healed, and many members of the Body who remain in exile from parishes, dioceses and communities who do not see the need to respond. It is to these communities we especially extend this invitation: Join us, this Lent, in our desert. And, to those who are already supporting neurodivergent members in the Body of Christ, as well as all our neurodivergent members far and wide: please, strengthen the Body for this journey with your prayers, too!

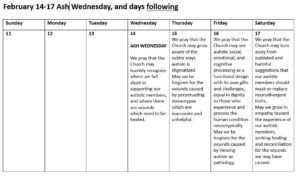

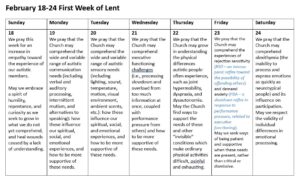

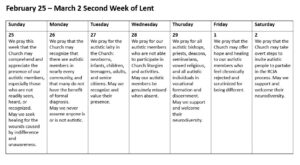

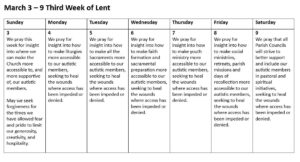

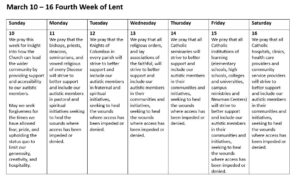

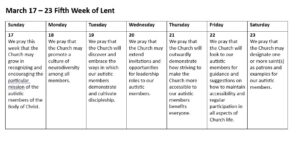

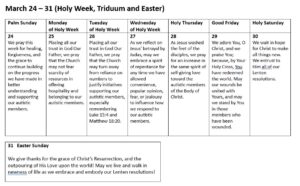

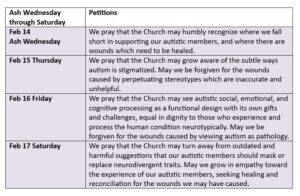

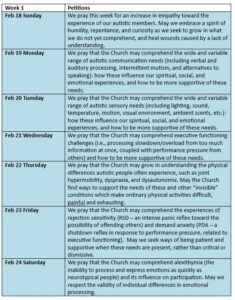

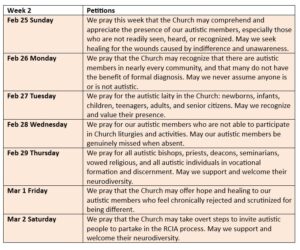

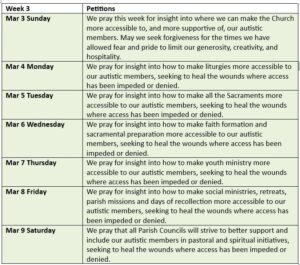

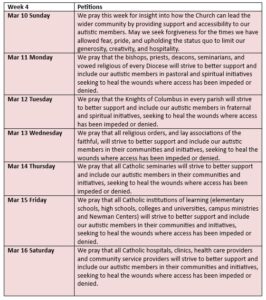

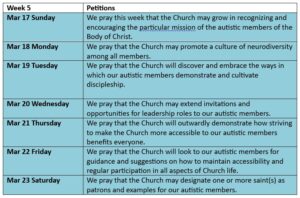

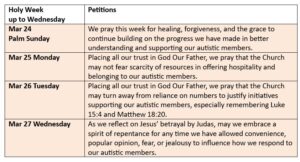

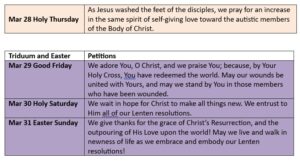

The following calendar serves as a map for such a journey. Each Lenten Day offers a prayer petition for pilgrims to draw ever closer to those of us who wait in hope for recognition, for reconciliation, and for our gifts and presence to be found acceptable by the rest of the Body.

On the Cross, the Good Thief – himself an exile from the community – made this prayer: “Jesus, remember me when You come into Your Kingdom.” This Lent, we ask Jesus to re-member us… to restore the exiled parts of His Body with circulation and nourishment and belonging.

Jesus promises “where two or more gather in My Name, I am there among them.” Be assured that this prayer calendar is being prayed by us here at Autism Consecrated. Whoever joins us in our prayer is united with us in Christ, and becomes a vital part of naming – and healing – the unfortunate effects of indifference, misunderstanding and outdated approaches to neurodiversity. May we pray together: JESUS, RE-MEMBER US!

– Aimée O’Connell, T.O.Carm., and Rev. Mark P. Nolette

Waldock, K.E. and Sango, P.N. (2023): Autism, faith and churches: The research landscape and where we go next. Autism and Faith, Vol. 20, No. 1. Retrieved on 2/2/24 from https://ojs.st-andrews.ac.uk/index.php/TIS/article/view/2578/1982.

Autism Consecrated grants full permission to print, share, save, forward, and distribute this calendar among individuals, groups and parishes.

View/Download Calendar in PDF Format:

Autism Consecrated grants full permission to print, share, save, forward, and distribute images of this calendar among individuals, groups and parishes.

2024 Lenten Prayers to Realize Autism’s Belonging in the Body of Christ

Grid Calendar Images (Click/tap through, and click/tap again to enlarge )

2024 Lenten Prayers to Realize Autism’s Belonging in the Body of Christ

List Format Calendar Images (Click/tap through, and click/tap again to enlarge )