ACAT 10: Putting Our Soul At Risk

What courses of action are harmful to our soul, or place our soul at risk?

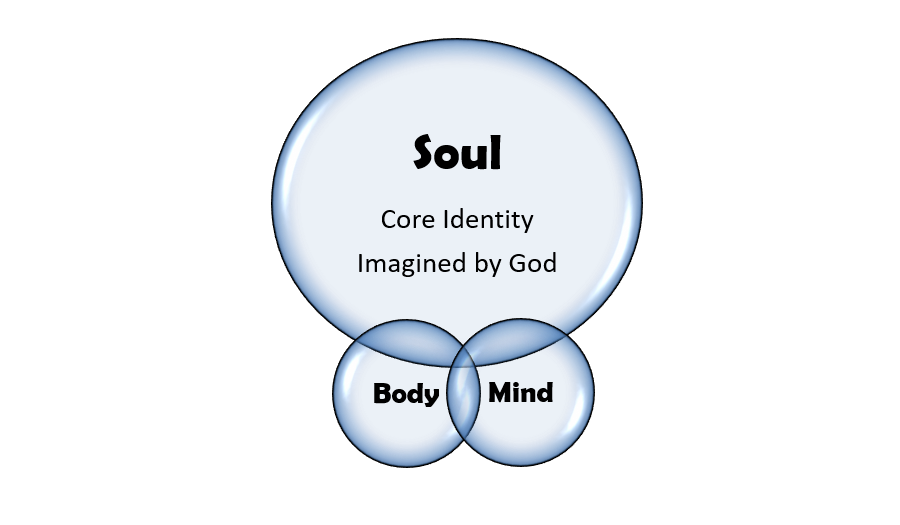

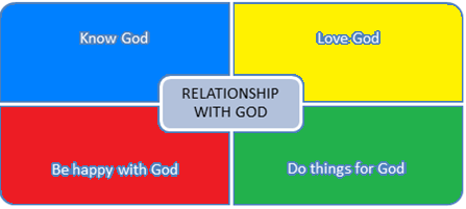

We continue our deeper look at the warning put forth by the Baltimore Catechism that neglecting to care for our soul leads us to lose God for all eternity. Even as appropriate as it may be to view that word “lose” as a sense of defeat, failure, or game-over, it is just as apt to consider that “lose” can also refer to something slipping out of sight, or not being where we can find it. Either way we are separated from God.

It would require a great deal more than annotation to delve into how a person’s actions can put the welfare of the soul at risk. Our task here is to give an overview and a sense of direction, rather than an exhaustive treatment.

Generally speaking: We place our soul in harm’s way any time we seek to remove it from God’s gaze.

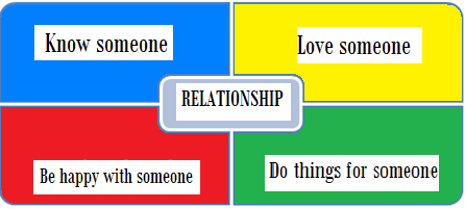

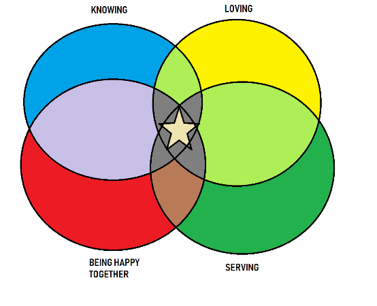

If we think of God’s gaze being filled with his love for us, then the things that would lead us to avoid God are those which are not good for our souls. Try as we might, we cannot think of any exceptions to this guideline (and it’s not for lack of trying!) Observe some examples that come to mind:

- Going against anything moral (lying, stealing, cheating)

- Purposefully calculating something that hurts another person

- Doing things we would not have God watch us do

- Avoiding God when we feel embarrassed, inadequate, frustrated or angry

That last one may surprise some of us. God does not punish us for reacting to our feelings, does he? No. But notice the example does not say to avoid the feelings or the reactions… it says that avoiding God in those moments puts our soul in harm’s way. God knows us and loves us in our strengths and our failings, so why would we feel the need to pull away when we are at our most vulnerable?

So very often we base our presence on what we bring to the room. And just as often we on the spectrum can feel overwhelmed, or empty, or unglued, or insecure, or shaggy around the edges, or grouchy, or tested to our very last limit… and be absolutely correct in declaring, “Leave me alone! I’m not very good company right now!”

Statements like this are not what would put our souls at risk. However, cultivating the habit of assuming God assesses us based on the quality of our successes, our moods or our cumulative merits is unfair to both ourselves and to God. God does not operate on human terms. He created us. He knows our operating systems, but is not subject to them. Taking our own space is perfectly fine for a time, but going to the extreme of shutting ourselves out of God’s gaze cuts off our spiritual oxygen. God knows us even at our worst moments, and loves us exactly as he loves us in our best moments. God’s love is not merit-based and does not fluctuate, either calculatingly like the stock market or erratically like the weather. God’s love is a constant… a given… an immovable absolute.

Even when we remove ourselves from his gaze.

The flip side here is that God’s love never wanes; and so, it also does not push, beg, force or chastise.

Are there consequences to the things we choose? Most certainly. Is there such a thing as Divine Justice? Most certainly. Does Divine Justice work the same way we understand human justice? Most certainly not. It can feel like there are no eternal consequences to the things we do, whether openly or in secret, whether we believe they count or believe they have no effect on any other person… but it remains those things which lead us to cut the connection which put our soul in mortal danger.