ACAT 21: A Study of Adam and Eve

Adam and Eve.

There cannot be many who have not heard some version of the Creation Story. Adam and Eve are humanity’s notorious duo, the first of our kind and the first to bungle things up. So numerous are the commentaries on these two that it borders on cliche to find their names in the Catholic Catechism. Yet, there they are, occupying the entire Lesson Five of the Baltimore Catechism, and likewise, our discussion for this week.

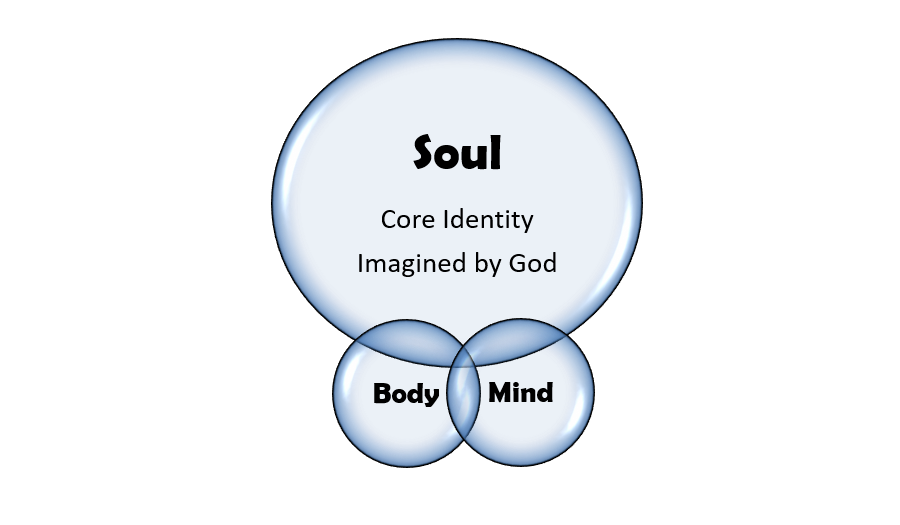

The Church believes Adam and Eve truly existed. They were created as man and woman were intended to exist, innocent of any corruption, fully expressing the rich gifts of their endowments of body, mind and soul by God, who loved the idea of them into flesh and bone and breath. Whether or not there was a botanical tree with literal fruit, or a spiritual construct embodied by metaphorical assignment, it is certain that God warned Adam and Eve of “partaking of the knowledge of good and evil.” God wished to preserve the innocence of the first man and woman by keeping their intellect focused on that which is good, beautiful and true. Could God have created anything that was evil, ugly or false? No… but He did create angels with free will, some of whom rebelled and set out to destroy and undermine God’s work. God likewise gave free will to Adam and Eve. While allowing them this freedom, he still intended them to live in purity and perfect balance. There would be no useful reason to follow any of the doings of the renegade angels.

As we know from the story, Eve was tempted by Satan to partake of that knowledge of good and evil, despite God’s warning. Satan asserted that God’s motive was to keep the man and woman from becoming a threat to God’s omnipotence. “You will not die if you eat the fruit,” Satan said. “Rather, you will become like God.” It was a clever exploitation of human nature: arouse curiosity, plant doubt and watch the rumor spread. Once Eve ate the fruit, Adam became curious and, using the disobedience of the other person as his rationale, followed suit. Part impulse, part calculated risk, part willingness to listen to a voice sowing seeds of distrust… our ancestors’ eyes were opened. Innocence was spoiled. Now, instead of seeing the good and the beautiful and the true, they saw it in terms of every way it could be perverted, distorted, exploited and ruined.

Horrified, Adam and Eve no longer felt safe. If goodness and beauty and truth could be corrupted, what guarantee did anyone have of anything? What once was seen in abundance suddenly became scarce. The present was no longer enough. Security became risk. In the presence of evil, God no longer seemed sufficient. In short: FEAR was introduced into humanity.

Our previous posts have emphasized a consistent theme: 1 John 4:18. Perfect love casts out all fear. And, in Adam and Eve, we see the inverse at work: fear deprives us of perfect love.

In the story, Adam and Eve cower in fear as they comprehend what they have done, and they can’t un-see the evil they now know. They understand why God instructed them to leave that fruit alone. What will God think? How could he love them now? Fear and doubt paralyze their once clear intellect. To make things worse, Adam and Eve now realize their very bodies can be used in perverse and corrupt ways, compared to the innocence and majesty of purpose they knew before seeing the ugliness of gluttony, lust and gratification. They covered themselves in shame.

Of course God knew what happened. With great sorrow, God watched His beloved man and woman fall away. Their responses betrayed them. Even God’s all-encompassing love fell into doubt in their minds. Fear gripped Adam and Eve… and they could not bear the perfect love of God. Perfect love casts out all fear… and so, Adam and Eve, enslaved by fear, were cast out on their own.

God did not abandon Adam and Eve. He continued loving them and all of their descendants no less than perfectly. With the institution of fear, however, humanity remains separated from God by the degree to which that fear holds sway over our minds.

Is there any hope for redeeming humanity’s relationship with God? Yes. In fact, God began laying the foundation for that redemption almost immediately. Through promises and covenants with the ones who trusted Him in spite of this primal fall, God led the way for the eventual birth of Jesus, the act through which God would become human himself and go before us in a story that would reverse every misstep of Adam and Eve, eventually taking on every conceivable fear and facing it himself in an incomprehensible demonstration of solidarity and desire to restore faith in Divine Love.

Remember, our task here is to annotate the Baltimore Catechism in ways that speak to the contemporary autistic mind. The Baltimore Catechism does a thorough job of explaining the “what” of the fall of humanity from grace. We aim, with the help of St. Thorlak’s theology of merciful love, to explain “why” – because, without a sense of why, the Catechism reads increasingly like a book of arbitrary rules… which speaks little to autistics and non-autistics alike.

Reference: Lesson Five, Questions 39-49.